This post was written by Dr Seb Gray and Dr Katie Knight, paediatric registrars, with consultant input from Dr Emma-Jane Bould

Acute severe asthma is one of the most common (and most anxiety inducing) presentations to frontline paediatric services. While most of patients stay at home managing well with simple bronchodilator therapy, up to 30% do not respond to initial treatment. If refractory to inhaled therapies, treatment is stepped up to IV therapies.

As well as IV salbutamol and aminophylline, IV magnesium is a powerful weapon in our arsenal when it comes to managing the acute severe asthmatic, and is becoming more widely used amongst emergency department paediatricians. Very rarely, escalation to intensive care +/- mechanical ventilation is required which can be challenging. Despite clear guidelines there is massive variation in practice around the UK and Ireland: a survey of 183 consultants in 30 centres revealed 28% used magnesium sulphate when escalating to IV bronchodilators but none reported giving it nebulised [1].

The current BTS/SIGN guidelines state:

Consider adding 150mg magnesium sulphate to each nebulised salbutamol and ipratropium in the first hour in children with a short duration of acute severe symptoms presenting with an SpO2 <92%

In this article, we review how magnesium works in the treatment of acute asthma, and assess the evidence that led to NMS being included in the BTS/SIGN guidance.

Magnesium sulphate – in brief

IV Magnesium sulphate improves pulmonary function and oxygen saturations, reduces hospital admissions, length of stay and PICU admission rate as well as being more effective than aminophylline in children aged 1-12 years [3-15].

Magnesium – physiology in acute asthma

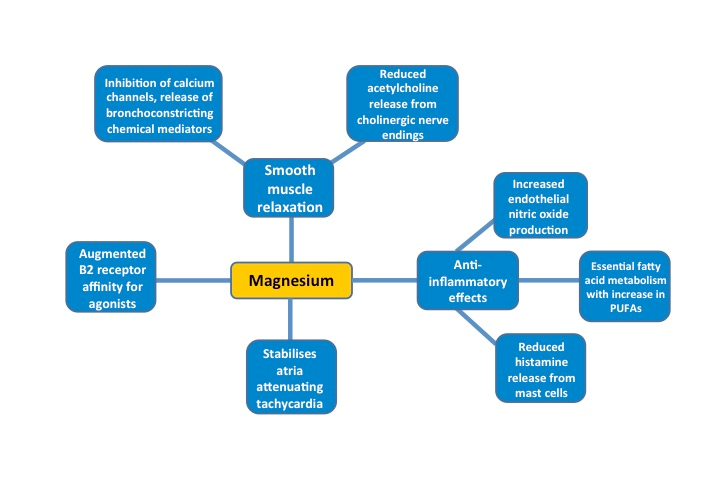

- Causes bronchial smooth muscle relaxation

- Anti-inflammatory effects

- Stabilises atria, reducing tachycardia

- Increases B2 receptor affinity for B2 agonists

It has been found that lower magnesium levels (particularly in polymorphonucleocytes and erythrocytes) correlate with asthma exacerbations [16-20]. One study has also shown that giving magnesium supplements reduced bronchial reactivity, weakened allergen induced skin responses and also improved control of asthma symptoms [21].

It has been found that lower magnesium levels (particularly in polymorphonucleocytes and erythrocytes) correlate with asthma exacerbations [16-20]. One study has also shown that giving magnesium supplements reduced bronchial reactivity, weakened allergen induced skin responses and also improved control of asthma symptoms [21].

Review of current evidence

A literature search was performed on OVID Medline 1946 – Present (July 2016) and Embase 1974 – Present using the following search criteria:

- Magnesium AND

- Nebuli?e* OR inhale* OR aerosol* AND

- Asthma* AND

- P?ediatric* OR child* AND

All articles were reviewed and further references found from manual review of bibliographies. Table summarising studies – click here

Findings

Reviews/ Meta-analyses: Focusing specifically on asthmatics up to the age of 18 years, the most recent Cochrane review in 2012 [22] included a total of 7 studies involving children [23-29] and two studies where they couldn’t determine the ages of participants (30,31). This Cochrane review concluded that there was not enough evidence to support NMS use.

Induced Bronchoconstriction Studies: Some studies have artificially created broncho-constriction in children (using metacholine) and then studied the effect of NMS (32-35). There were conflicting results between studies, as some suggested that NMS worked best when given simultaneously with salbutamol while others found it worked best alone. Translating the reversibility of iatrogenic bronchoconstriction to clinical practice is tricky – the pathophysiological process is likely to be different, and we know that β2 receptor number and function varies with asthma exacerbations [35]. The results of these studies are therefore of questionable relevance.

Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs): The results of nineteen RCTs involving asthmatics up to the age of 18 years are summarised in the table below. There are pretty significant problems when you try to compare these varied studies; most are only partially reported (conference abstracts) and only 12 of the studies looked exclusively at children. Some studies pitched NMS against β-agonists, others compared IV to nebulised magnesium, and others added NMS to standard therapy. Also, the doses of NMS varied (up to seven-fold between studies) and there was a wide range in number and frequencies of administration.

Many different outcomes were measured, with varied asthma severity scores and lung function tests. In a cohort of predominantly severe asthmatics, many assessed the effectiveness of NMS by admission rate, which does not seem the most accurate way of judging how useful this therapy might be.

Table summarising studies – Click here

Why was NMS added to the 2014 BTS/SIGN Guidelines?

In short, the MAGNETIC study – the largest of its kind to involve only children (aged 2-16 years; n=508) with acute severe asthma – was ultimately responsible for the change in guidance [42]. MAGNETIC showed a better Yung asthma severity score in children who received NMS every 20 minutes for the first hour compared to placebo (in addition to salbutamol and ipratropium bromide in both cohorts). A larger benefit was seen in more severe exacerbations, and those with a shorter duration of symptoms.

In short, the MAGNETIC study – the largest of its kind to involve only children (aged 2-16 years; n=508) with acute severe asthma – was ultimately responsible for the change in guidance [42]. MAGNETIC showed a better Yung asthma severity score in children who received NMS every 20 minutes for the first hour compared to placebo (in addition to salbutamol and ipratropium bromide in both cohorts). A larger benefit was seen in more severe exacerbations, and those with a shorter duration of symptoms.

Safety

Theoretical side effects include hypotension, muscle weakness, respiratory fatigue and apnoea. In clinical practice these are incredibly rare and giving magnesium via nebuliser (with less potential to cause systemic side effects) should reduce the risk of these even further. The Cochrane review (of 896 patients receiving inhaled magnesium) did not identify any significant adverse effects – no child in this review experienced hypotension [22]. Only one subsequent study reported any adverse effects (flushing, vomiting, headache and transient hypotension) although these were not found to be statistically significant compared to controls [42].

Conclusion

Overall, studies have identified NMS as safe – but comparing a group of studies which are so different in their approaches is always challenging. The MAGNETIC trial (which demonstrated a benefit to acute severe asthmatic children with a short duration of illness) was successful in changing national guidance. We use this study as a guide for the doses we use in practice as per the BTS/SIGN guidelines. (151mg isotonic magnesium sulphate; 2.5ml of 250mmol/l, tonicity 289mOsm).

The benefits of nebulised versus IV magnesium are clear – it’s quick to administer, has fewer systemic side effects and you don’t have to cannulate a child who is probably already distressed.

However, it does have disadvantages. The dose delivery of nebs compared to IV is less consistent, and relies on respiratory effort and function for effective delivery. Future research will need to look at dosage, frequency, duration and timing to optimise benefits. In the meantime, escalation to IV magnesium should still be considered if nebulised magnesium has already been given and not led to an improvement. Also, around 30% of children requiring IV treatment for wheeze or asthma are under two years old [46] and as yet there are no studies looking at NMS use in this group of children – more research is needed on potential benefits of NMS in the under twos.

Whether various ongoing studies will change current clinical advice remains to be seen. Currently, many clinical networks are not yet following the BTS/SIGN guidance for the use of NMS in acute severe asthma (47). This may be due to the updated guidelines being relatively recent. Increased usage may require a cultural change in asthma management which will take some time to filter down into practice.

It’s possible that with an excellent safety profile and proven benefit, we will see NMS become more common in paediatric asthma exacerbation management as we become more comfortable and familiar with its use.

This is an excellent review many thanks.

You don’t mention that the magnetic trial (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24429155) showed a very minor (non significant) reduction in a composite asthma score (4.7 vs 4.9) at 60mins but no effect on clinically meaningful outcomes such as admissions / time in hospital. Isn’t this clear evidence that you should not be using it?

I disagree that: http://www.harboruclapsych.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Psychiatry_Residency_Manual_2016-2017.pdf

Friendly, Gudrun

Great article thank you. I presented a little project I did on the years of its use in children’s hospitals in the UK. Rates are still fairly low but increasing quite rapidly. We’ve just added it to our guideline in Plymouth.

almost a year on Tim, and still waiting for it to be included in the guideline….